by Laura López Paniagua

I saw in his hand a long spear of gold, and at the iron's point there seemed to be a little fire. He appeared to me to be thrusting it at times into my heart, and to pierce my very entrails; when he drew it out, he seemed to draw them out also, and to leave me all on fire with a great love of God. The pain was so great, that it made me moan; and yet so surpassing was the sweetness of this excessive pain, that I could not wish to be rid of it. The soul is satisfied now with nothing less than God.

Is the Spanish mystic Teresa of Ávila’s description of her religious experience pornographic? Is it obscene? About half a century after she wrote these words, Gian Lorenzo Bernini completed a sculpture capturing this precise moment of holy petit-morte that became one of the most iconic works of Western art: Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647–52). Saint Teresa’s surrendered countenance with her half-open mouth and her eyes rolling back is a literal representation of an orgasm — yet her face is just the pinnacle of a mountain of aroused cloth. It is as if the saint, soul, flesh, and habit, had become a giant tumescent flower suspended in the mystical spheres of sexual otherworldliness. Why did Bernini choose to translate the moment of ecstasy into these exact tangible forms? Is there a relationship between spirit, flesh, and fabric?

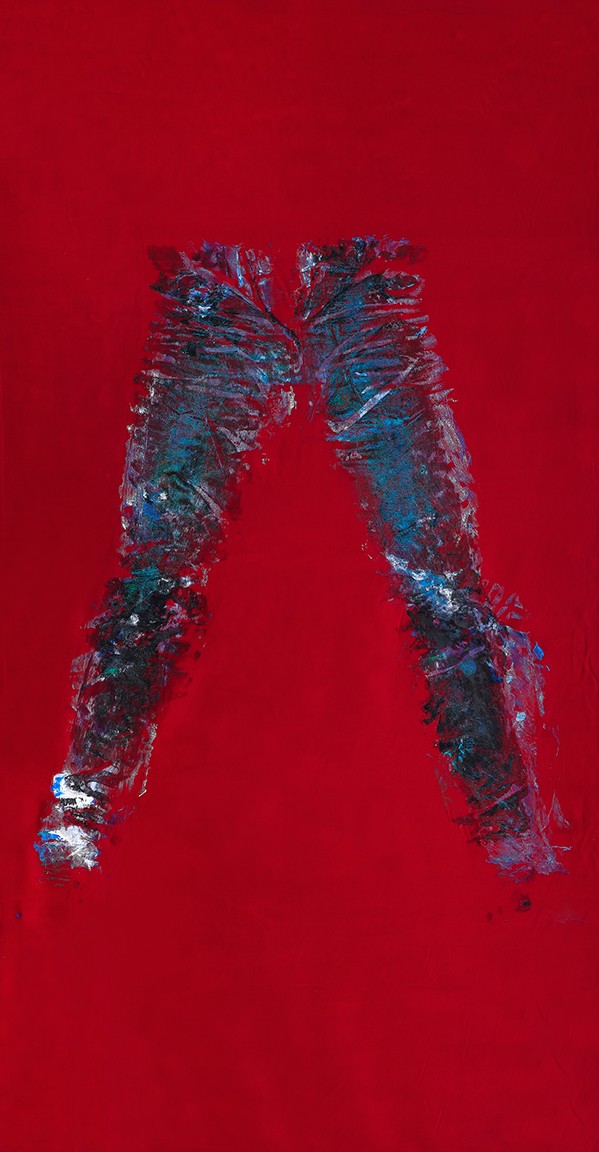

Aura Rosenberg’s series of velvet body imprints from the late 80s and early 90s follows a long tradition of artworks that convey the eroticism of cloth that can be traced both in the East and the West. An instance of this textile proclivity through an Eastern sensitivity can be found in the Japanese Shunga genre of the Edo period. Shunga prints depict explicit sexual acts in which the kimonos worn by the characters play a fundamental role. They seductively guide the eye to every detail of the scene, which becomes equally suggestive: the flower, the pattern, the window, the tatami, and frame the exposed body parts — a delightful discovery among the soft dance of moving textiles. The imprints shown in Behind the Curtain follow a similar series of paintings in which naked bodies were covered with paint and transferred onto cloth. During this early period of her career, Rosenberg was inspired by modernist painting, attempting to introduce figures into the composition without rendering them, by printing from naked bodies directly onto the surface. These paintings pursue the same goal but are more explicitly erotic. Here, the trace of the nude physique is absent, and only the clothing has been printed on the velvet, which paradoxically makes the body even more present as the observer is tacitly invited to mentally reconstruct its ghostly presence. White Shirt on Black Velvet, coquettishly opens on the lower part like a lover alluringly lifting their garment. On Blue Jeans, the legs of the trousers appear twice, once open and once closed, and the fly is down, bringing to mind the sexy cover of Andy Warhol's Rolling Stones' Album Sticky Fingers (1971), which could be literally unzipped. These works attest that an erotic trance never depends on what is done, shown, or uttered, but rather, on the drifting veils that reveal and conceal, the restraint and release of the strings, and the silence that cloaks the sound of a blurred word.

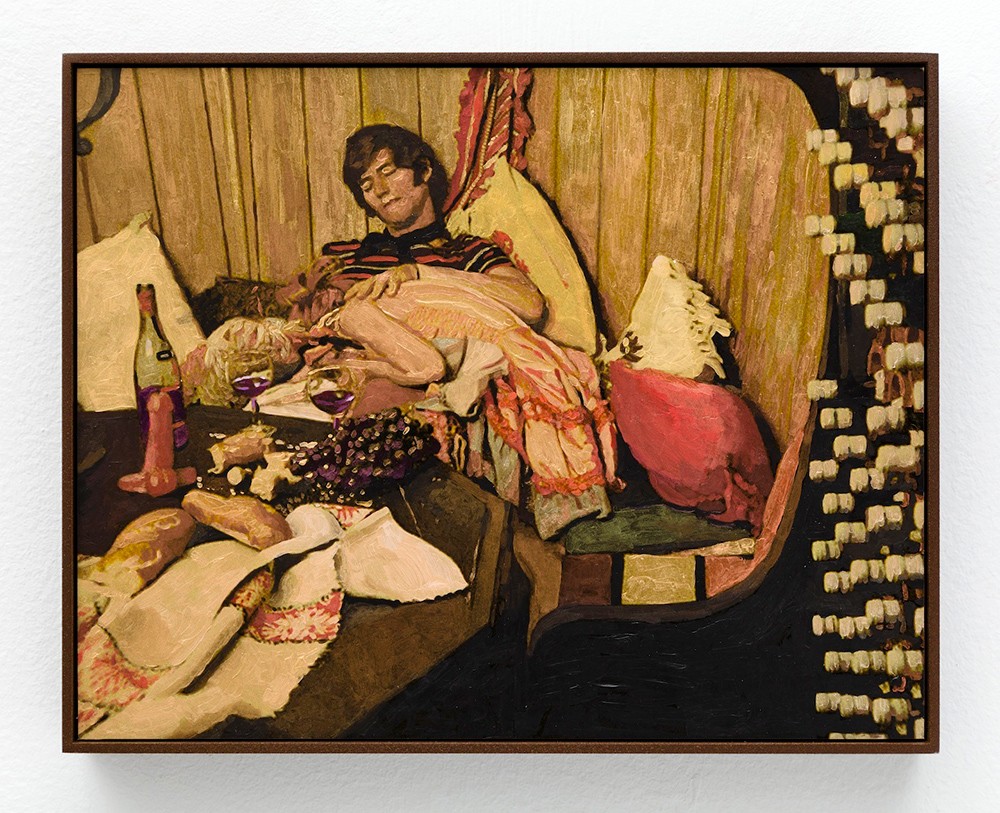

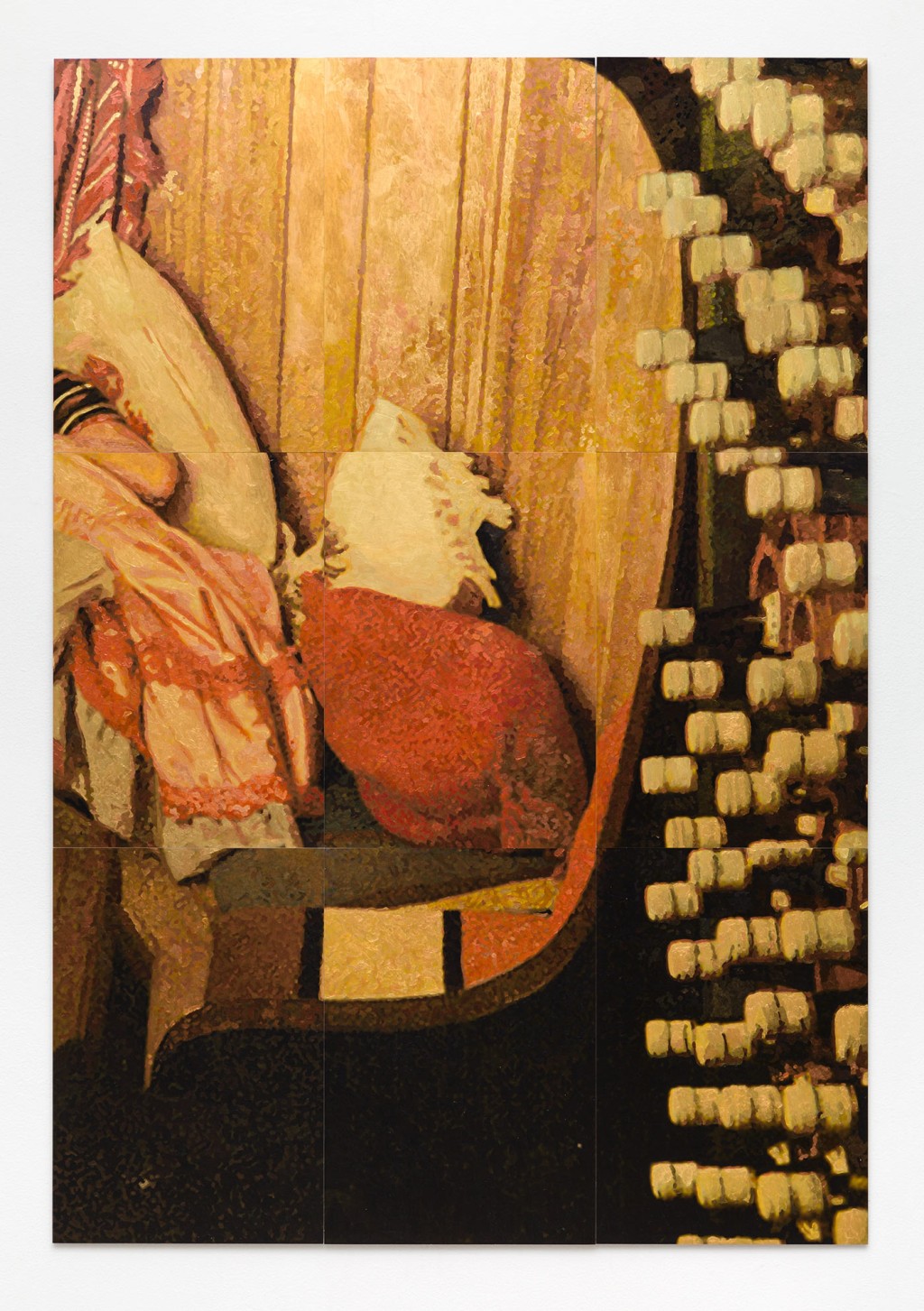

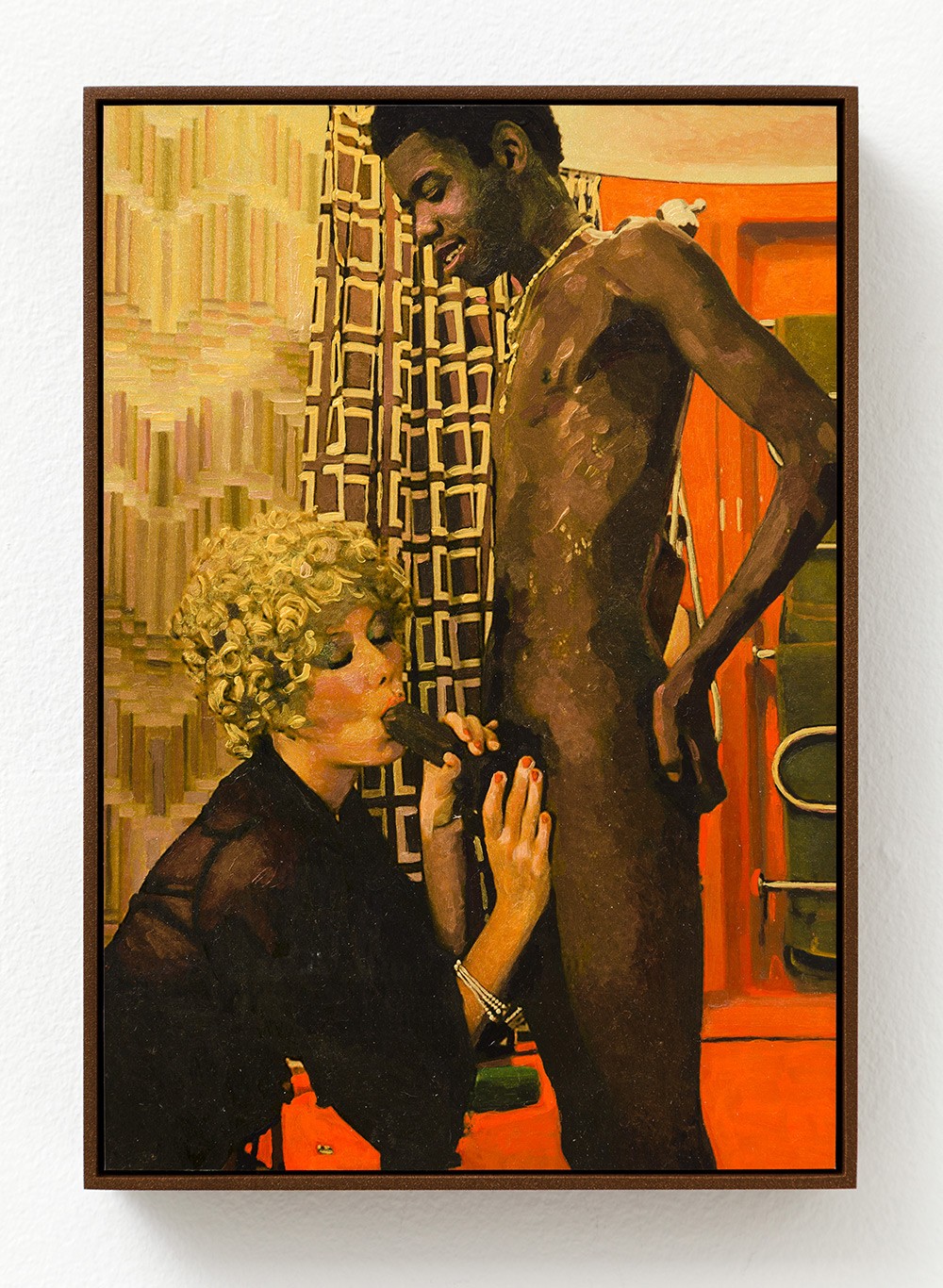

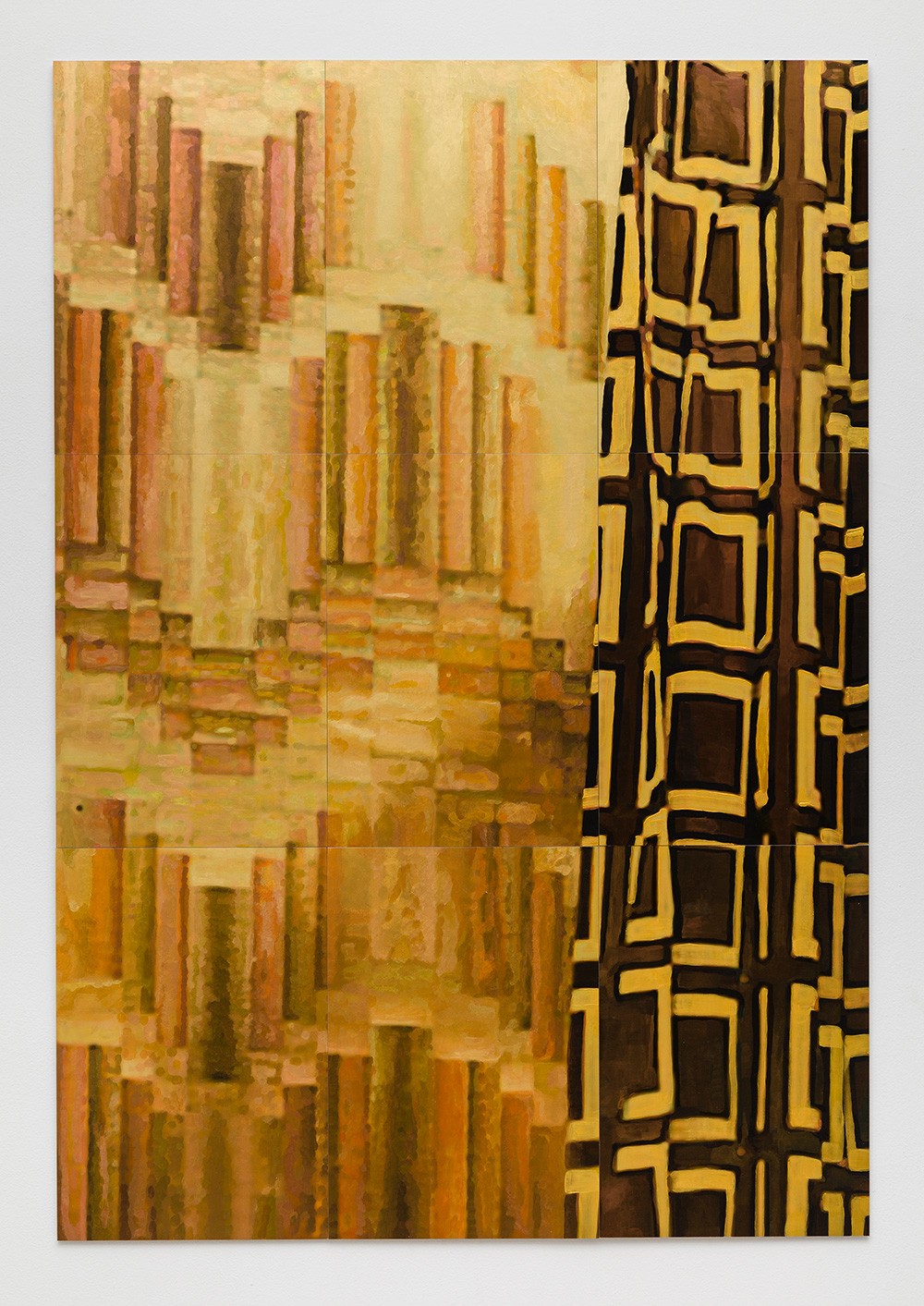

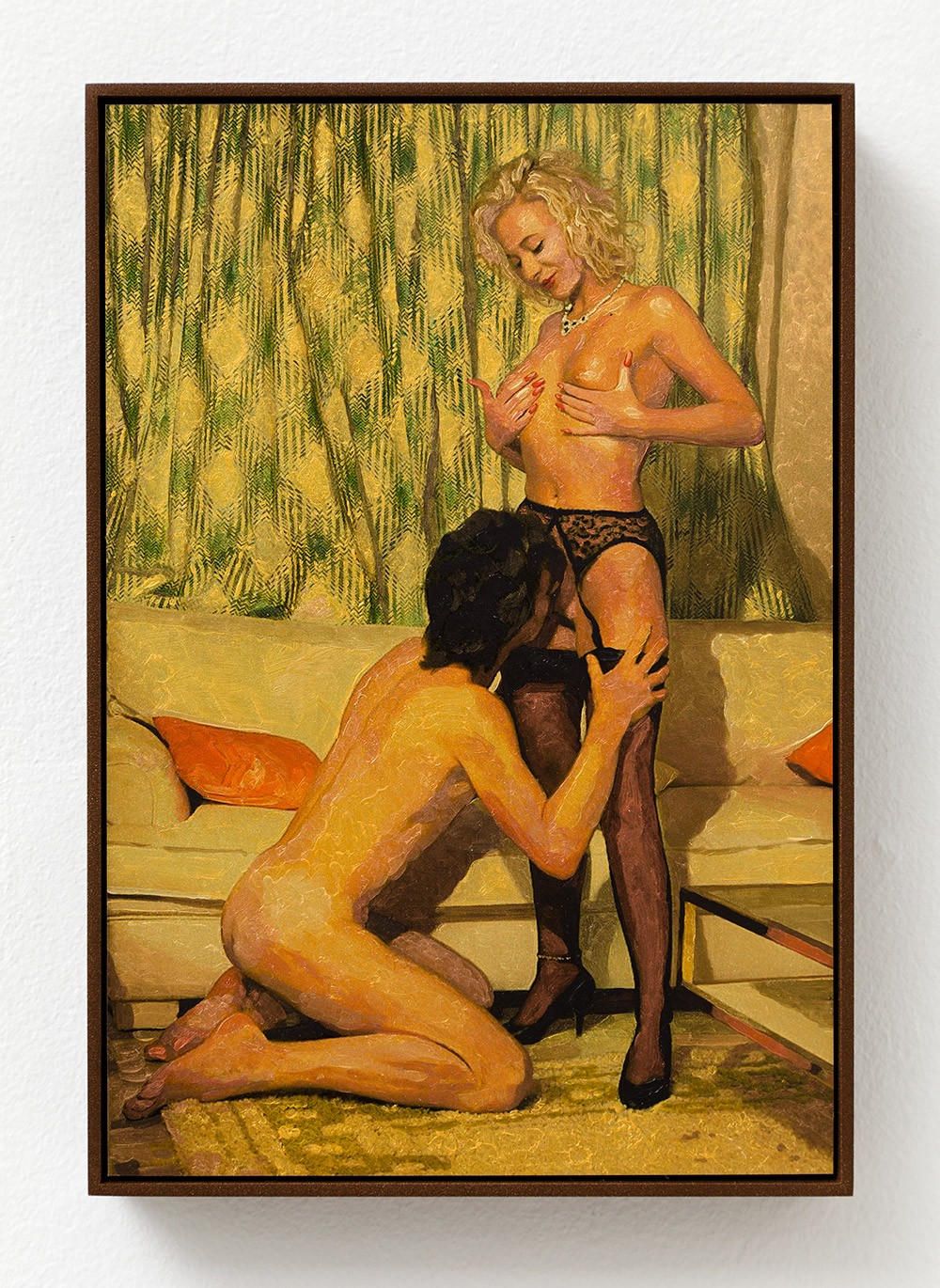

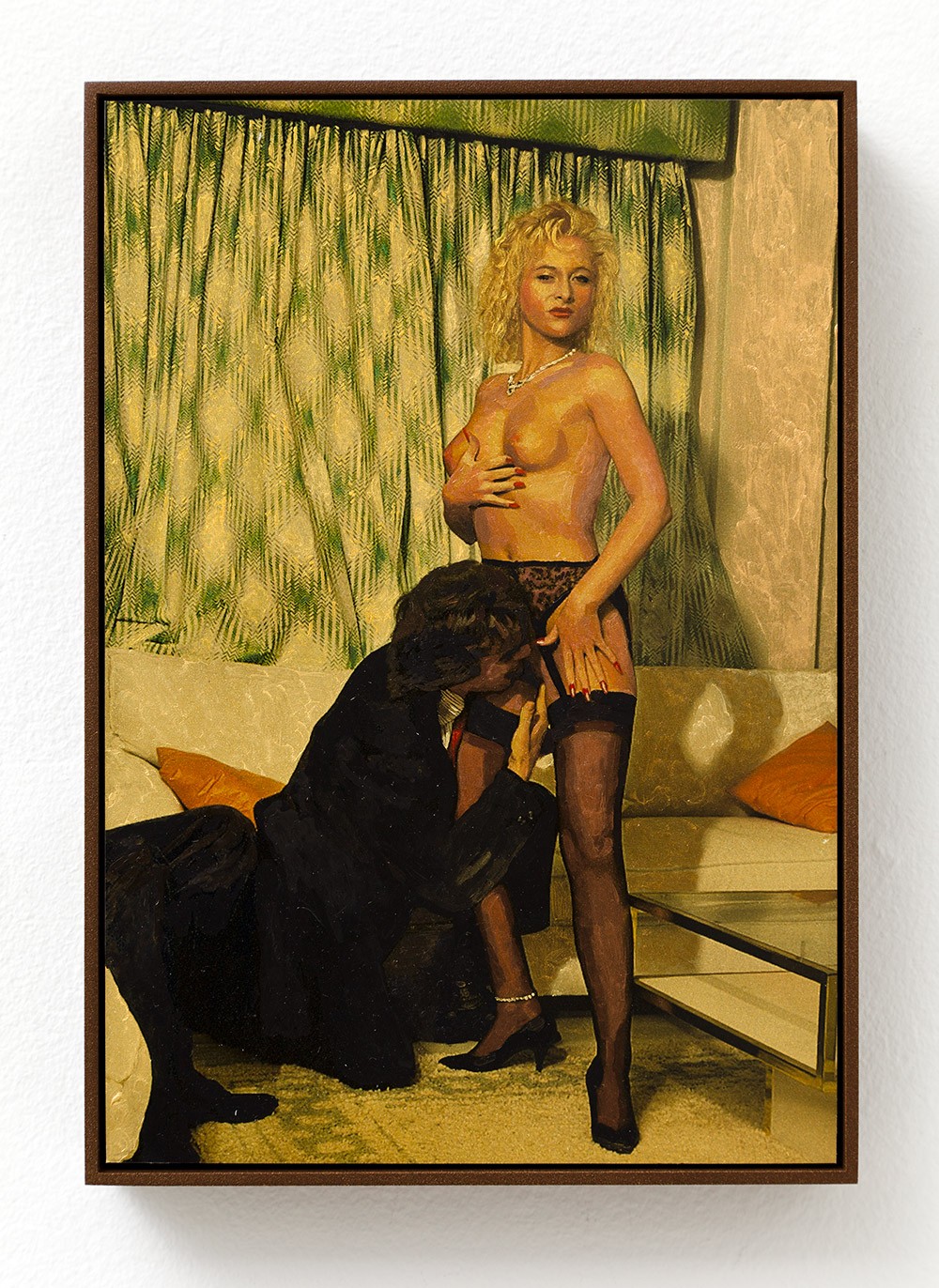

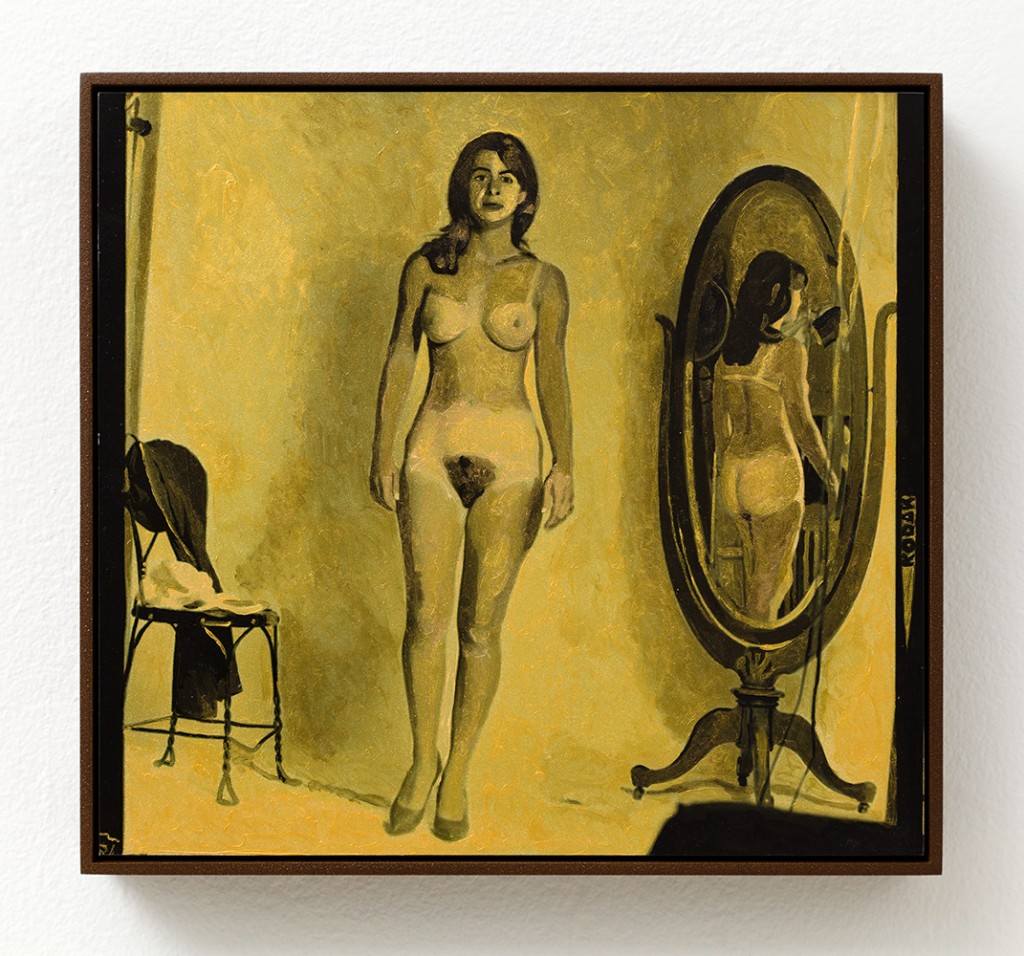

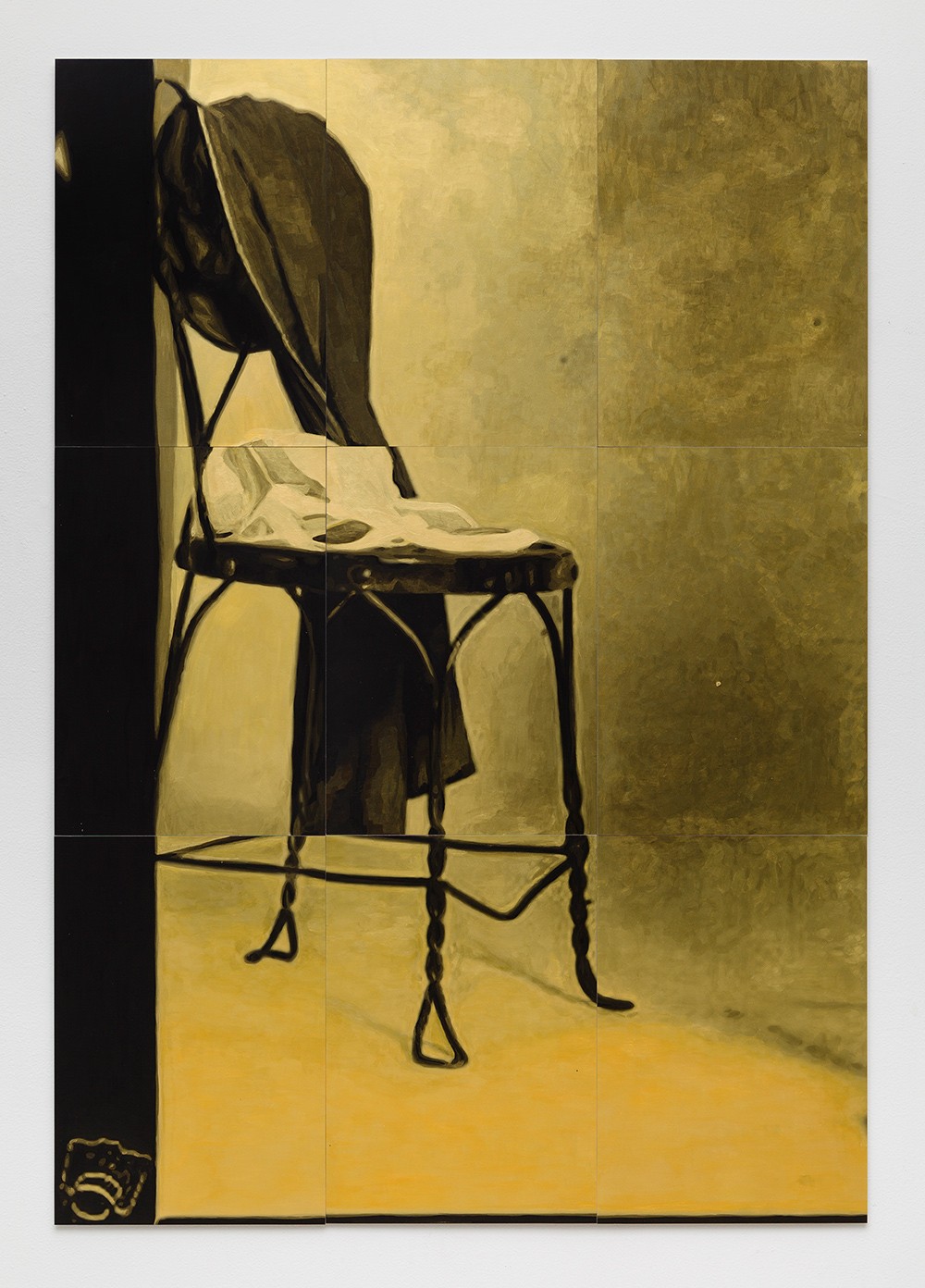

In this scenario, the cloth becomes charged with sensuality as an element that creates a barrier between the bodies, but that can turn into ersatz flesh, becoming then the object of desire itself - a fetish. Would, therefore, the obscenity of erotica be found, not in the acts or the bodies themselves, but in the objects around them that become magically (or mystically) imbued with desire? This was D. H. Lawrence’s thesis in his 1929 paper Pornography and Obscenity, in which he put forward a later contested etymology of the concept of the “obscene” in Greek theatre as the elements outside the “scene” or action . Rosenberg’s series Scene/ Obscene (2013) draws on Lawrence’s derivation of the term, giving a nod to classical drama. The paintings of this series conjure up the so-called “Golden Age” of pornography (the 70s and early 80s) — a concept playfully echoed in the work Scene Chair Tanlines Camera (2014), a photograph printed on golden panels and painted over with golden paint. All of the source material of the series depicts salacious acts in specific settings: usually living rooms or bedrooms adorned with the colorful geometric patterns of the time, Moroccan décor, and where liquor bottles and tacky glassware abound. These details are the true protagonists of the works, and in them, curtains like the one depicted in Obscene Gold Green Curtain (2014) play a star “obscene” role. They not only evoke theatre representations explicitly, but they also convey the eroticism of fabric, here as a purely abstract and fetishistic presence.

Teresa of Ávila speaks of the body as a prison of the soul , yet her description of her ultimate communion with God is unequivocally expressed in carnal terms. This dichotomy between body and soul and their respective association with dirt and purity is present not only in Catholicism but in Western thought as a whole. In The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music (1872) Friedrich Nietzsche addressed this polarity identifying two opposing tensions in this culture: the Dionysian (base, erotic, colored), and the Apollonian (idealized, rational, monochromatic) -- the second dominating the arts, especially during Neoclassicism. This was expressed in what art historian Reginald Wilenski refers to as “Greek prejudice”: the idea that Greek and Roman cultures were as restrained, white, and pure as the colorlessness presumed of their statues — an assumption proved wrong by the myriad of sexually explicit artworks unearthed with the excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii during the eighteenth century. Unlike Neoclassicists, Nietzsche didn’t regard classical culture as the epitome of the Apollonian, but saw Greek tragedy as the interplay of both forces, thus advocating a more integral and profound view of the human condition.

Rosenberg’s Lenticular Works (2018-ongoing) could be seen to address the Greek prejudice both in terms of form and meaning. In the series Statues Also Fall in Love, black & white photographs of Classical, Renaissance and Neoclassical sculptures that the artist took in Europe and the U.S. turn into found pornographic imagery through the use of a lenticular lens. This technique allows for Nietzsche’s Apollonian and Dionysian poles to be represented on a single surface: the marble sculptures that follow the Greek canon of bodily beauty, and mostly represent mythological themes, shift into pornographic photographs, which, in contrast, are less refined, and even caricaturesque. This is especially true in the latest instances of the series (2023). Exhibited for the first time on this occasion, the sculptures, all shot in Italy turn into pinkish contemporary nudes, culled from online websites. Works like Capitoline Venus (2023) or Capitoline-Hercules Killing Hydra (2023) not only raise questions about art history and its lineages but also about the changing notions of beauty and eroticism. Can these models be seen to represent contemporary ideals? Pornography is made for instant sexual consumption, but these bodies somehow seem to elude eroticism despite their accessibility — or precisely because of it. Could the cold marble of blooming Saint Teresa whisked in folds, paradoxes, and petals, still be much hotter?